What Does Hedging Mean? How Does It Work? Strategies & Examples

Editor's Note: Options are not suitable for all investors. Options involve risks, including substantial risk of loss and the possibility an investor may lose the entire amount invested in a short period of time. Please see the Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options.

Table of Contents

When investors talk about hedging, it refers to a common risk-management strategy that involves taking a position with one investment to help offset the potential risk of loss in another investment.

For example, bonds and cash may be used to counterbalance potential risk exposure from the equities portion of a portfolio.

Hedging methods vary widely, depending on what the investor views as the main risk factors in their portfolio. Common hedges include derivatives, like options and futures contracts, or investments in commodities like gold or oil, or fixed-income investments.

Key Points

• Hedging is a risk-management strategy where one investment is used to offset potential loss in another investment.

• Common hedging methods include derivatives (options, futures), commodities (gold, oil), or fixed-income investments.

• Hedging acts like an insurance policy, protecting holdings in the event of risk, but it also comes with costs in time and money.

• Various hedging strategies exist, such as diversification, spread hedging, forward hedging, and more.

• Hedging is viable for retail investors, ranging from simple diversification to more complex options strategies.

What Is Hedging?

Hedging can be defined as making an investment to reduce the risks associated with another investment. For some investors, protecting a portfolio against downside risk can be as important as generating returns, whether investing online or with a brokerage.

Often, some investors may hedge to protect themselves in the event that their investments decline in value, in order to limit potential losses. While technically speaking hedging means investing in a particular security to offset the risk from a related security, there are many ways to hedge.

One common hedge is through basic diversification: choosing an investment whose price movements historically do not correlate to the main investment (e.g., when fixed-income securities are used to hedge against equities).

Also, many investors go about hedging with options contracts, purchasing securities that move in the opposite direction of the main investment.

Recommended: Options Trading 101

How Does Hedging Work?

In many ways, hedging investments works like an insurance policy. A homeowner may purchase insurance to protect their home from fire or other potential risks. That insurance policy costs money, which is an investment of sorts. So if there’s a fire, that insurance may protect the homeowner from greater losses.

Hedging is like that insurance policy. Investors trading stocks and other securities can’t protect against all risks. But with the proper hedges in place they can protect their holdings from possible risk factors. But, like insurance, those hedges cost money to make.

Hedging may also reduce an investor’s exposure to the upside of the other elements of their portfolio.

Pros & Cons of Hedging

To understand the pros and cons of hedging, consider an airline, whose fuel costs impact the company’s profitability. The airline may have a trading desk whose sole job is to buy and sell options and futures contracts related to crude oil, as a way of protecting the company against the shock of a sudden upturn in oil prices.

Pros of Hedging

The first pro of hedging for the airline is that those financial derivative instruments allow it to project its fuel costs with some degree of certainty at least a few months into the future.

The other pro of hedging comes when the price of oil skyrockets for some reason. In that case, the airline knows it can buy oil at the previously predetermined price in the oil futures contracts it owns.

Cons of Hedging

The con of hedging would be the constant ongoing expense of maintaining it. The airline has to pay for the oil futures contracts, even if it never exercises them. Futures contracts expire on a regular basis, requiring the company to continue buying them. And if fuel costs don’t go up, then it’s likely that the futures contracts the airline buys will be worthless when they expire.

Recommended: Stock Trading Basics

The company also has to devote personnel to maintaining the portfolio of its hedges, to buy and sell the derivatives, and to periodically test the hedge to make sure it continues to protect the company as the markets shift. For the airline that represents money and talent that is diverted away from its core business.

The analogy for investors is clear. While hedges can protect an investment plan, they also come with a cost in time and money. And it’s up to each investor to determine whether the cost of a hedge is worth the protection it offers.

Hedging Examples and Strategies

There are several ways that investors can use hedging to help protect their portfolios.

Diversification

Portfolio diversification is probably the best known and most widely used risk management strategy. It relies on a broad mix of investments within a portfolio to help protect the portfolio from facing too large of a loss if one investment loses value.

A diversified portfolio will hold several distinct asset types to reduce its exposure to any single investment risk. For example, investors may balance out the risk of a stock holdings with bond securities, since bonds tend to perform better in markets where stocks struggle.

Spread Hedging

Spread hedging is a risk-management strategy employed by options traders. In this strategy, a trader will buy and/or sell two or more options contracts on the same underlying asset with the goal of limiting their losses if the price of the asset moves against them, typically in exchange for limited profit potential.

In a bull put spread, for example, a trader might purchase one put option with a lower strike price and sell another put with a high strike price with the hope of benefitting from a rise in the underlying asset’s price, while capping losses if the price falls.

Forward Hedge

Forward contracts are financial derivatives used mostly by businesses to protect themselves from changes in the value of a currency. For the purchaser, the contract effectively fixes the rate of exchange between two currencies for a period of time. The airline example discussed above is a forward hedge.

Delta Hedging

Delta hedging is a strategy used by options traders to reduce the directional risk of price movements in the security underlying the options contracts. In the strategy, the trader buys or sells options to offset investment risks and reach a delta neutral state, in which the investment is protected regardless of which way the asset price moves.

Tail Risk Hedging

Tail risk hedging refers to an array of strategies whose goal is to protect against extreme shifts in the markets. The strategies involve a close study of the major risk factors faced by a portfolio, followed by a search for the least expensive investments to protect against the most extreme of those risks.

For example, an investor overweight U.S. equities might purchase derivatives based on the Volatility Index, which tends to negatively correlate to the S&P 500 Index.

Binary Options Hedging Strategy

In a binary options hedging strategy, the investor buys both a put and a call on the same underlying security, each with a strike price that makes it possible for both options to be in the money at the same time. Binary options only guarantee a payout if a predetermined event occurs.

Forex Hedging

A forex hedge in the forex market refers to any transaction made to protect an investment from changes in currency values. As a hedge, they may be used by investors, traders and businesses. For example, since GBP/USD and EUR/USD typically have a positive correlation, you could hedge a long position in GBP/USD with a short position in EUR/USD.

Another example of forex hedging is purchasing a currency-hedged ETF. Doing so gives investors the protection of a forex hedge against the investments within their ETFs, without having to actually purchase the hedge on their own.

Hedging for Hyperinflation

Inflation hedges are those investments that have outperformed the market when inflation is a major factor in the economy. While every inflationary period is different, with various global, market and macroeconomic factors in play, investors have historically found shelter — and sometimes growth — during inflation by investing in certain assets.

Some investments that have a reputation as inflation hedges include precious metals such as gold, and commodities like oil, corn, beef, and natural gas. Other inflation hedges include alternative investments, such as REITS and real estate income.

Dollar-Cost Averaging

Some investors view dollar-cost averaging, which involves investing a set amount of money at preset intervals regardless of market performance, as a way to hedge against market volatility. That’s because dollar-cost averaging, by definition, means that you’re buying investments when they’re both high and low — and you don’t have to worry about trying to time the market.

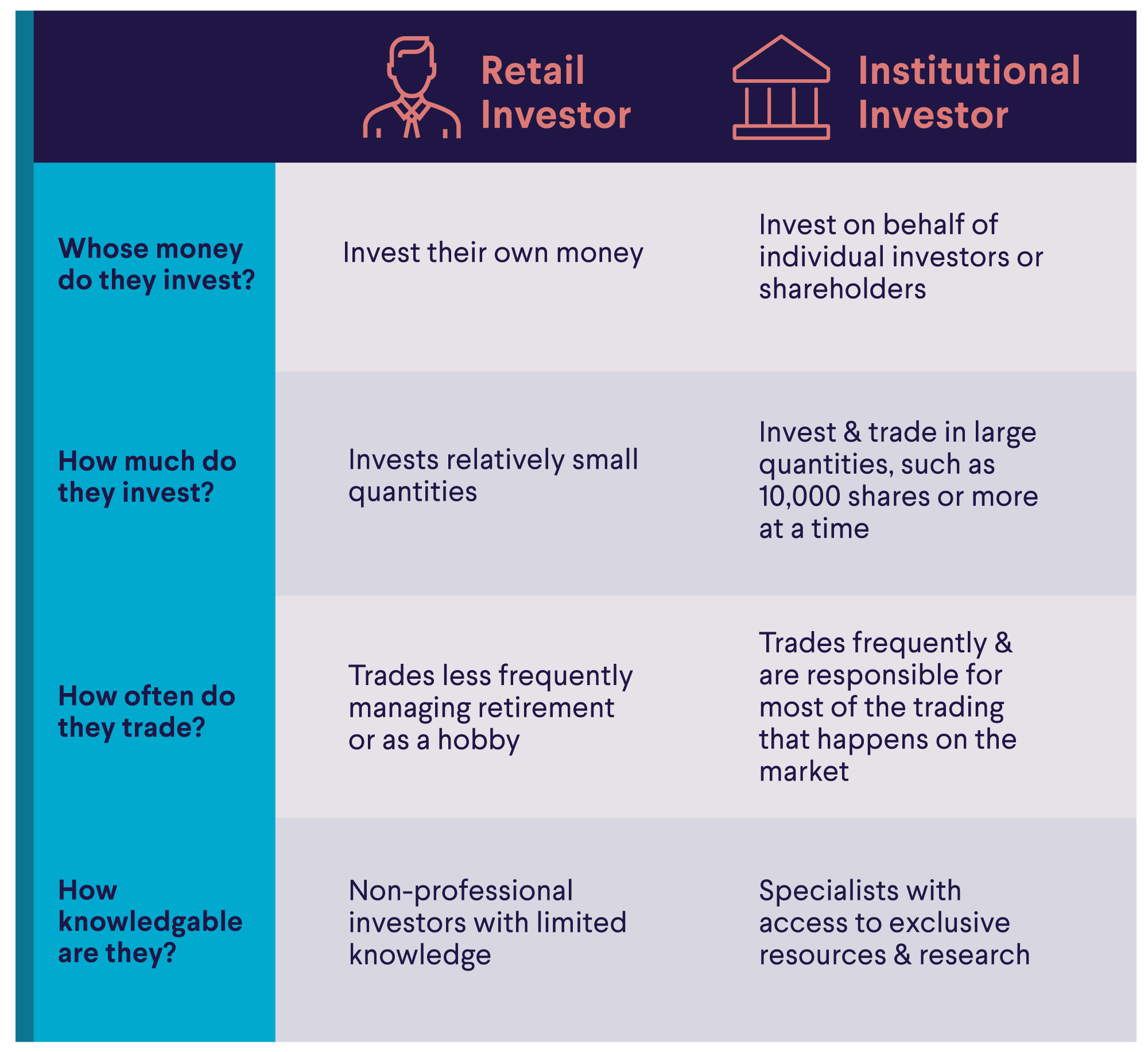

Is Hedging Viable for Retail Investors?

Yes. While some hedging involves complicated options strategies, you can also hedge your portfolio by simply making sure that you have diversified holdings. If you’re investing to protect against certain risks, such as inflation or interest rate increases, that’s also an example of hedging.

The Takeaway

Hedges are investments, often derivatives, that help protect investors from risk. Hedging is a common strategy to use certain types of securities to offset the risk of loss from another security.

However, it’s possible to hedge some investments without investing in derivatives. Building a diversified portfolio of stocks and bonds, for example, or investing in real estate to protect against inflation risk are also examples of hedging.

Invest in what matters most to you with SoFi Active Invest. In a self-directed account provided by SoFi Securities, you can trade stocks, exchange-traded funds (ETFs), mutual funds, alternative funds, options, and more — all while paying $0 commission on every trade. Other fees may apply. Whether you want to trade after-hours or manage your portfolio using real-time stock insights and analyst ratings, you can invest your way in SoFi's easy-to-use mobile app.

FAQ

How does hedging work in simple terms?

Hedging works by counterbalancing the risk of an existing investment. For example, if you own stocks, you might use options or bonds to reduce your overall exposure to stock market volatility, thereby limiting potential downside.

What are some common methods for hedging?

Diversification is one widely used risk management strategy. Other common hedging methods include derivatives (options, futures), commodities (gold, oil), or fixed-income investments.

What is the downside of hedging?

Hedging requires time and effort to set up the appropriate hedge for your investments, and there may be associated costs as well. In addition, because hedging focuses on avoiding downside risks, it may limit a certain amount of upside.

Photo credit: iStock/Rossella De Berti

INVESTMENTS ARE NOT FDIC INSURED • ARE NOT BANK GUARANTEED • MAY LOSE VALUE

For disclosures on SoFi Invest platforms visit SoFi.com/legal. For a full listing of the fees associated with Sofi Invest please view our fee schedule.

Options involve risks, including substantial risk of loss and the possibility an investor may lose the entire amount invested in a short period of time. Before an investor begins trading options they should familiarize themselves with the Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options . Tax considerations with options transactions are unique, investors should consult with their tax advisor to understand the impact to their taxes.

Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs): Investors should carefully consider the information contained in the prospectus, which contains the Fund’s investment objectives, risks, charges, expenses, and other relevant information. You may obtain a prospectus from the Fund company’s website or by emailing customer service at [email protected]. Please read the prospectus carefully prior to investing.

S&P 500 Index: The S&P 500 Index is a market-capitalization-weighted index of 500 leading publicly traded companies in the U.S. It is not an investment product, but a measure of U.S. equity performance. Historical performance of the S&P 500 Index does not guarantee similar results in the future. The historical return of the S&P 500 Index shown does not include the reinvestment of dividends or account for investment fees, expenses, or taxes, which would reduce actual returns.

Dollar Cost Averaging (DCA): Dollar cost averaging is an investment strategy that involves regularly investing a fixed amount of money, regardless of market conditions. This approach can help reduce the impact of market volatility and lower the average cost per share over time. However, it does not guarantee a profit or protect against losses in declining markets. Investors should consider their financial goals, risk tolerance, and market conditions when deciding whether to use dollar cost averaging. Past performance is not indicative of future results. You should consult with a financial advisor to determine if this strategy is appropriate for your individual circumstances.

Investment Risk: Diversification can help reduce some investment risk. It cannot guarantee profit, or fully protect in a down market.

Financial Tips & Strategies: The tips provided on this website are of a general nature and do not take into account your specific objectives, financial situation, and needs. You should always consider their appropriateness given your own circumstances.

An investor should consider the investment objectives, risks, charges, and expenses of the Fund carefully before investing. This and other important information are contained in the Fund’s prospectus. For a current prospectus, please click the Prospectus link on the Fund’s respective page. The prospectus should be read carefully prior to investing.

Alternative investments, including funds that invest in alternative investments, are risky and may not be suitable for all investors. Alternative investments often employ leveraging and other speculative practices that increase an investor's risk of loss to include complete loss of investment, often charge high fees, and can be highly illiquid and volatile. Alternative investments may lack diversification, involve complex tax structures and have delays in reporting important tax information. Registered and unregistered alternative investments are not subject to the same regulatory requirements as mutual funds.

Please note that Interval Funds are illiquid instruments, hence the ability to trade on your timeline may be restricted. Investors should review the fee schedule for Interval Funds via the prospectus.

SOIN-Q325-090

Read more